All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

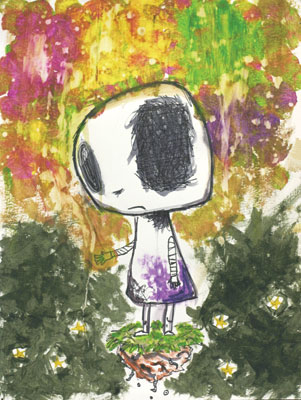

Capacity of Pain

At five a child’s only worry was the monster hiding under the bed. Unfortunately, mine was a monster festering inside my left frontal lobe. Her name was Cancer. I couldn’t run to my parents for comfort. I couldn’t hide under the blankets. I couldn’t get rid of her by turning the lights on. I couldn’t grow out of it. She would always be there, just lurking. Cancer was a part of me. She was the death sentence I would carry with me for the rest of my life. I was five. The world that was so much bigger than me, so much more beautiful than I could imagine, confined to a singular white box. I would be spending the rest of my life in and out of that cold, fluorescent lit hospital room that smelled of bleach and stainless steel. I hated that hospital. I hated those twin sized beds with paper thin blankets and pillows filled with nothing but tissues. I hated that flavorless slop that even the Nurses would pucker their noses at in disgust. I hated being the youngest in the ward, the most pitied. But what I hated most of all, was myself.

******

It was the middle of Kindergarten, during our second recess. I was running, playing, chuckling, and all of a sudden I was on the ground. None of the children comprehended why I couldn't quit shaking. I was raced to the hospital; the only thing I could recall were noisy commotions and fluorescent lights and somebody instructing me to continue breathing. ”In, Out, In, Out…” There wasn't much else I could do. It felt like an unending length of time before I was set down on a table. Regardless, I couldn't move. Something beeped uproariously alongside me; alerting everyone around that my heart was still beating. All I wanted was it to stop. However, I couldn't talk, couldn’t move either. I laid there, motionless, numb, terrified; wishing it all to just go away.

Maybe it was the impacts of the medications, or the unadulterated dread; however this is the place my memory ceases. My parents filled in the spaces, and I framed my own viewpoint from that. The seizure halted, yet now they needed to discover why it had begun. Here I was, five years of age, convulsing on a table, and they were completely puzzled. I was put into this enormous machine and they scanned my body, concentrating on my cerebrum. That’s where they found her, youthful and putrefying, loaded with shrewdness. I wish they had never let me know she was there. I wish they had treated me like the little child I was and just lie to me. I wish they had told me everything was okay.

I was five. I didn't comprehend that I was dying, I didn't get the idea of it. The world I knew was flipped upside down. The word meant nothing to me. Dying? I couldn't fathom it. The prospect that this life I had: the sky, the grass, the clouds; could be so effortlessly taken away from me was excessively intricate for me, making it impossible to understand.

I was five. I didn't know why my parents were crouched together on the other side of the room, crying. I didn't know why the doctor was holding my hand and giving me the saddest eyes, talking so delicately I could scarcely hear. I didn't comprehend why so many people felt sorry for me. Why so many people congratulated me on how fearless I was or how strong. I wasn't fearless. I wasn't strong. I was lost and befuddled. The doctor called her “Stage One Primary Brain Cancer”. It ought to have sounded alarming, destructive, yet to me they were just words. She meant nothing to me.

I was five and I had a death sentence.

Cancer. For what life I had left, that word would set a blaze to my tongue and burn holes in my mouth. No other word could make my family tense like that one. It became taboo from that point on. No one wanted to speak it or even think of it, but for the next eleven years it would be the only word I’d ever hear.

I lost my hair. Chemotherapy, they called it. I remember practicing how to say it when I was bored. Che-mo-ther-apy. My brother, who was only nine at the time and just as confused as I, would insist on holding my hand during every dose of treatment. Che-mo-ther-apy. My teachers would be so impressed with my vocabulary.

The following couple of years, I was the butt end of the joke. I would stroll up to somebody, attempt to say hello, and they would shout. "Cooties! She has cooties!" The children in different grades began playing along, as well. I never thought I would want to go back to those painfully bright white rooms, but at least when I was there, people tried to make me comfortable. Exactly when the teasing had finished, exactly when I believed that perhaps everything would be alright, it happened once more. It was the first year of middle school. Strolling through the corridors, chuckling and grinning, and afterward I was flat on my face. Someone shouted, and I was back to sleeping on paper thin mattresses, in that same small, fluorescent lit room. Everyone has a certain capacity of pain, and I had reached mine.

Stage Two Primary Brain Cancer. I thought she had gone away. I thought I had finally grown out of her. I was wrong. She had become more awful, and we missed the window for operation. I was back to medicines and being hairless, and flavorless food; yet, this time I understood everything. I understood what wasn't right with me, that there was this thing developing in my mind, draining the life out of me such as a bloodsucker. I understood that treatment was temporary. I understood that she would be there for life. I still couldn’t run from her, she would always be with me. Chemotherapy was more than a word to me, it had an importance. I didn’t need my brother to hold my hand anymore. I didn’t need the nurses to rub my back as I continually vomited my meals back up. I understood everything. All I needed was for her to go away. But that was only a vacant dream.

******

There are two perspectives people take on Cancer. There are those of us who see her as a test and those of us who see her as a condemnation; the essential qualification is whether we see ourselves as victors or casualties. I saw myself as a victim for most my life, up until just about two years ago I was on and off treatment. Nothing lasted...nothing but her. She stood strong, triumphant over every attack we had attempted. She was eternal, and I simply wasn’t. I lost my motivation to fight back, but my parents prevailed. Then it happened. She left. Nothing felt so unreal. I remember thinking “This can’t be true. You’re lying to me. She’ll never actually be gone.” But then they showed me the scans. Her dark matter was no longer within the frame of my cerebrum. She truly was gone.

Thirteen years, she had overstayed her welcome. Thirteen years, I struggled with hating her, hating myself for creating such a monster. Thirteen years were lost. Thirteens years of constant nausea and trips to the hospital. Thirteen years of pity. No more. I had a choice to be the causality or the victor. For thirteen years I made the wrong one. I hated myself for thirteen years. Not anymore. I decided to love myself. I’m the victor. I won.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

Cancer Survival