All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

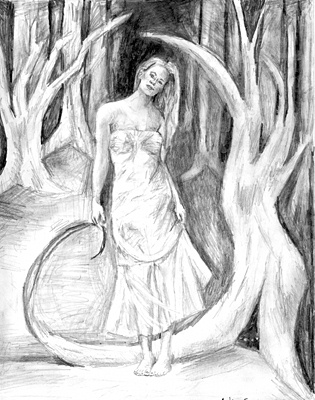

The Ginkgo Tree

I once knew this girl who planted weeds. She lived on the edge of the cape, where the grass gave way to nothing but sharp rocks and rough sand. The cliffs there jut over the colorless ocean on one end and dip into the gray beach on the other, and even the drift wood trees and the beach grass seem bleached.

Nothing in this town has color to it. It’s all been washed away.

The girl, she had this little rickety house on the cliff. Nobody knows where it came from, and in the shadowed corners of drug stores and flower shops it’s a constant subject of gossip. Most believe it just sprang from the ground: ugly, spindly, and always there as far back as anyone could remember, though no one had ever seemed to notice it before her. The house itself was another weed, just like the ones she planted.

This girl, she took all of these ugly, spindly plants and put them in little clay-red pots, then covered them up with dirt, so lovingly you would think they were her children. I’ve heard her sing lullabies on more than one occasion. Some of her weeds even had flowers.

Most just had thorns.

For awhile she even kept a pot of little purple honey suckles, gray leaves shooting out of them at all the wrong angles, crippling almost.

And this girl, she took all of these potted weeds and she placed them at her white picket fence and her white picket gate, (which weren’t so much as white anymore as they were slate.) They lined her cobble stone walkway, crowded around her stairs, sat on her porch, and thrived between the shutters of her windowsill. These gray, ugly plants, that looked half on the verge of death, overflowed her yard. They were often accompanied by tufts of crab grass and wild onions, which she let grow freely through her lawn and garden, because to her they were beautiful.

Beautiful because they were strong.

Her name was Daisy St. Marshall Malone, or Indigo Newberry, or Bianca Lupe de Martinez, she told me, the first time I caught her on my front lawn. She had been kneeling in the dirt, the knees of her jeans covered in grass stains, mud caked under her fingernails from digging the giant hole around my mailbox. By her side was a pot full of dandelions she had been carefully unearthing for the last half hour.

She wanted some yellow to lighten up the garden now that the honeysuckle had died, she said.

We used to take long walks on the beach together, she and I. She walked with a terrible limp, and used a grizzled, old can to move around. It was difficult on the sand, but she loved the beach, and refused to stay home. She loved everything, Daisy did…or Indigo…or Bianca Lupe. She talked constantly about how she loved the desolation of the land here, right up to the rocks that pushed rudely against the water.

She loved its lack of color. Its anti-chromatic layout.

Only the hardiest of nature’s creatures could survive here, she said, as she struggled through the sand on her little cane. That’s why she loved the weeds so much.

She told me, taking a break to wiggle her toes in the sand, that there was this Ginkgo tree that used to grow outside her apartment when she lived in the city. That tree had been ugly and smelly: straight, uniform, and covered in thousands of little nuts that smelled oddly of rotten apricots and hot vomit. Everyone had hated that tree except for her.

Sitting on the beach, letting the iron waves roll over her legs, then her waist, hardly noticing her clothes becoming soaked, she tells me that the weather here reminds her of the city. It’s gray all the time, whether it’s rain or shine.

The only difference is we’re not afraid to show it. The city, she says, tries to hide itself by blinding people with lights and flashy colors. Here, there’s nothing to hide it, so it doesn’t even try. Honesty is the best policy, after all.

She says that the Ginkgo tree had been planted many years ago, and had never stopped. Its roots had slithered between the cracks in the sidewalk, just like the weeds do between the rocks here, and there it had staid. It had been swung on by school children, carved by bored and romanced teenagers. It had been bent and bruised and abused, but that Ginkgo had kept going, till it was tall and strong. The fruits clustered on its branches had been smelly as sin, but she had loved that tree.

Every time she told me this, I had to wonder.

That Ginkgo tree, she continued, had been surrounded by all sorts of dandelions. This was two days after I caught her digging holes in my yard, potting my weeds to place on her porch. From where we stood on the beach, I could still see the yellow brightening the gray wash painted over the cliff.

She told me, as we took that hobbling, difficult walk on the sand, that the city had cut down the Ginkgo at the request of the angry tenants in her apartment complex. They were tired of the rotten smell, and the view that wasn’t quite appealing enough to make up for the flaw. Though the city had laws against cutting down trees due to certain laws, they relented under the loop hole that, because of the sidewalk it had destroyed, it was “hazardous” to the residents. She had sat in that tree for days, refusing to come down. She had slept nestled in its gnarled branches, praying for a miracle.

When she told me this, I had to wonder more, because the look in her eyes was of sheer pain and fright.

When it died, she said, she brought dandelions to its grave every day.

And she began to cry, losing her grip on her cane and letting it drop to the sand.

This girl who planted weeds and loved the gray, desolate land and the terrible weather and her Ginkgo tree: Daisy St Marshall Malone/Indigo Newberry/Bianca Lupe de Martinez, was ill. Terminally ill. One day the holes stopped showing up in my yard, staring out my window at the dingy clouds rolling overhead, I could feel something was wrong.

So I dug through the garage awhile and found an old flower pot and a trowel, and dug up some dandelions. Here I was, destroying my own yard, and the irony almost overtook me with both a fit of tears and a fit of laughter. But I knew where the weedy house on the cape grew, so I went to visit.

She laughed when I brought them to her. She smiled at me so dazzlingly I almost didn’t notice how her bones pressed against her ashen skin, making her arms and hands twist like knobs. She had to move several pots over to make room for her new dandelions on the bedside table, but that only made her laugh harder.

They’re my most favorite of all, she told me, her cheekbones casting gaunt shadows against her face as her smile grew.

She told me her Ginkgo tree-she used what little wood she could salvage of it to form a walking stick, and she took it with her every time she went out. Having the Ginkgo beside her gave her strength. It had grown from the weeds to its full and glorious potential until it had been forced down, long before its time should have come.

She pointed to her little gray cane, leaning against the bedside table. A cobweb was strung between its handle and the table’s leg; she couldn’t walk anymore.

She was just like the Ginkgo, she told me. She spent her whole life trying to be strong, to stand high when no one thought she could, but just like her mighty Ginkgo tree, she would be cut down when she should be strongest, long before she could wither on her own.

Daisy St. Marshall Malone/Indigo Newberry/Bianca Lupe de Martinez, when she died a couple months ago she looked just like a Gingko tree, all limbs and twisted knot holes. I could only laugh when they buried her in the sand below the rocks her house grew from. I just didn’t know what else to do. Nowadays I keep people from ripping out the weeds that thrive along the cracks of her rocky grave. I took the Gingko stick home with me, and I use it whenever I walk: down to the flower shop to pick up pots, where I still hear hints of gossip from older lips, and always along the beach in the evenings, letting the steely water soak through my shoes, hoping to keep the memory of her alive beside me.

My yard is nothing but holes now. I still remember to bring her dandelions every single day.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 2 comments.

5 articles 0 photos 72 comments

Favorite Quote:

“Don't forget - no one else sees the world the way you do, so no one else can tell the stories that you have to tell.”<br /> ― Charles de Lint, (from his book,The Blue Girl)